Welcome

We hope to offer a place you can refer to when in question about many aspects of a healthy sex life. The most important factor in bringing about a healthy, safe and enjoyable sex life is education and communication. Continue reading

Welcome

We hope to offer a place you can refer to when in question about many aspects of a healthy sex life. The most important factor in bringing about a healthy, safe and enjoyable sex life is education and communication. Continue reading

TIBB-E-NABVI

The subject is too vast to cover in the space allotted for a single speech. The study of tibb-e-nabvi, the body of herbal, holistic, and naturopathic medicine known to the Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.S.) and the people of his time and culture, has enjoyed a resurgence. As scientists have investigated the chemical composition of foods and their role on the biochemical level in maintaining health and preventing and curing diseases, Continue reading

WARNING!!!!!

The article below contains an image of an aborted foetus (fetus). Viewer’s discretion is advised!

Abortion in Islam is a crime after the first 120 days – in Islam!

The sections of this article are:

1- Abortion in the Noble Quran.

2- Allah Almighty “breathes” from His Spirit into the foetus.

– The Hadiths claim that after the first 120 days of the Foetus formation, Allah Almighty blows from His Spirit into it.

– Scientific Discoveries that confirm the Hadith.

3- Warning from doing abortion to all women in the Noble Quran.

4- Conclusion.

Mom and Baby Basics

Your world is about to change in countless, wonderful ways with the arrival of your baby. This new era in your life comes with specialized “to do” and “to buy” lists — but neither is necessarily long or expensive. In fact, the most important things you can give your child are love, time and patience — and those are free!

Nevertheless, you’ll want to purchase some items to make life a little easier for you and your baby. To get you started, we’ve assembled this list of useful items and helpful shopping tips.

•Maternity Clothes

•Nursing Bras and Pads

•Car Seats

•Baby Clothes

•Blankets

•Diapering

•Diaper Bags

•Slings or Infant Carriers

•Co-Sleepers

•Rocking Chairs

•Breast Pumps

•Books

•Developmental Toys

•Bath Supplies

•Bouncer Seats

•Strollers

•High Chairs

Hepatits C Virus

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a small (55-65 nm in size), enveloped, positive sense single strand RNA virus in the family Flaviviridae. Although Hepatitis A virus, Hepatitis B virus, and Hepatitis C virus have similar names (because they all cause liver inflammation), these are distinctly different viruses both genetically and clinically.

Contents

1 Structure

2 Genome

3 Replication

4 Genotypes

5 Vaccination

6 Current Research

7 References

8 External links

Continue reading

Plastic surgery is a medical and cosmetic specialty interested in the correction of form and function. While famous for aesthetic surgery, plastic surgery also includes a variety of fields: craniofacial surgery, hand surgery, burn surgery, microsurgery, and pediatric surgery. The word “plastic” derives from the Greek plastikos meaning to mold or to shape; its use here is not connected with the synthetic polymer material known as plastic.

Contents

1 History

2 Techniques and procedures

3 Reconstructive plastic surgery

4 Cosmetic surgery

5 Plastic surgery sub-specialities

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 Further reading

10 External links

History

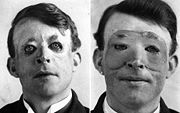

Walter Yeo, a British soldier, is often cited as the first known person to have benefitted from successful plastic surgery. The photograph shows him before (left) and after (right) receiving a skin graft performed by Sir Harold Gillies in 1917.

Plastic surgery was being carried out in India by 2000 BC.[1] Sushruta (6th century BC) made important contributions to the field of Plastic and Cataract surgery.[2] The medical works of both Sushruta and Charak were translated into Arabic language during the Abbasid Caliphate (750 AD).[3] These Arabic works made their way into Europe via intermediaries.[4] In Italy the Branca family of Sicily and Gaspare Tagliacozzi (Bologna) became familiar with the techniques of Sushruta.[4]

British physicians traveled to India to see Rhinoplasty being performed by native methods.[5] Reports on Indian Rhinoplasty were published in the Gentleman’s Magazine by 1794.[5] Joseph Constantine Carpue spent 20 years in India studying local plastic surgery methods.[5] Carpue was able to perform the first major surgery in the Western world by 1815.[6] Instruments described in the Sushruta Samhita were further modified in the Western world.[6]

The Romans were able to perform simple techniques such as repairing damaged ears from around the 1st century BC. Due to religious reasons they didn’t approve of the dissection of both human beings and animals, thus their knowledge was based in its entirety on the texts of their Greek predecessors. Notwithstanding this Aulus Cornelius Celsus has left some surprisingly accurate anatomical descriptions, some of which —for instance, his studies on the genitalia and the skeleton— are of special interest to plastic surgery.[7]

The Egyptians were also one of the first people to perform plastic cosmetic surgery.

In 1465, Sabuncuoglu’s book, description, and classification of hypospadias was more informative and up to date. Localization of urethral meatus was described in detail. Sabuncuoglu also detailed the description and classification of ambiguous genitalia (Kitabul Cerrahiye-i Ilhaniye -Cerrahname-Tip Tarihi Enstitüsü, Istanbul)[citation needed] In mid-15th century Europe, Heinrich von Pfolspeundt described a process “to make a new nose for one who lacks it entirely, and the dogs have devoured it” by removing skin from the back of the arm and suturing it in place. However, because of the dangers associated with surgery in any form, especially that involving the head or face, it was not until the 19th and 20th centuries that such surgery became commonplace.

Up until the techniques of anesthesia became established, all surgery on healthy tissues involved great pain. Infection from surgery was reduced once sterile technique and disinfectants were introduced. The invention and use of antibiotics beginning with sulfa drugs and penicillin was another step in making elective surgery possible.

In 1792, Chopart performed operative procedure on a lip using a flap from the neck. In 1814, Joseph Carpue successfully performed operative procedure on a British military officer who had lost his nose to the toxic effects of mercury treatments. In 1818, German surgeon Carl Ferdinand von Graefe published his major work entitled Rhinoplastik. Von Graefe modified the Italian method using a free skin graft from the arm instead of the original delayed pedicle flap. In 1845, Johann Friedrich Dieffenbach wrote a comprehensive text on rhinoplasty, entitled Operative Chirurgie, and introduced the concept of reoperation to improve the cosmetic appearance of the reconstructed nose. In 1891, American otorhinolaryngologist John Roe presented an example of his work, a young woman on whom he reduced a dorsal nasal hump for cosmetic indications. In 1892, Robert Weir experimented unsuccessfully with xenografts (duck sternum) in the reconstruction of sunken noses. In 1896, James Israel, a urological surgeon from Germany, and In 1889 George Monks of the United States each described the successful use of heterogeneous free-bone grafting to reconstruct saddle nose defects. In 1898, Jacques Joseph, the German orthopaedic-trained surgeon, published his first account of reduction rhinoplasty. In 1928, Jacques Joseph published Nasenplastik und Sonstige Gesichtsplastik.

The U.S.’s first plastic surgeon was Dr. John Peter Mettauer. In 1827, he performed the first cleft palate operation with instruments that he designed himself. The New Zealander Sir Harold Gillies, an otolaryngologist, developed many of the techniques of modern plastic surgery in caring for those who suffered facial injuries in World War I. His work was expanded upon during World War II by one of his former students and cousin, Archibald McIndoe, who pioneered treatments for RAF aircrew suffering from severe burns. McIndoe’s radical, experimental treatments, lead to the formation of the Guinea Pig Club. Plastic surgery as a specialty evolved tremendously during the 20th century in the United States. One of the founders of the specialty, Dr. Vilray Blair, was the first chief of the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. In one of his many areas of clinical expertise, Blair treated World War I soldiers with complex maxillofacial injuries, and his paper on “Reconstructive Surgery of the Face” set the standard for craniofacial reconstruction. He was also one of the first surgeons without a dental background to be elected to the American Association of Oral and Plastic Surgery (later the organizations split to be renamed the American Association of Plastic Surgeons and the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons) and taught many surgeons who became leaders in the field of plastic surgery.

Techniques and procedures

Common techniques used in plastic surgery are: Liposuction, Breast Augmention, Eyelid surgery, Face lift, Tummy tuck, Collagen injections, Chemical peel, Laser skin Resurfacing Rhinoplasty, Forehead lifts.

In plastic surgery the transfer of skin tissue (skin grafting) is one of the most common procedures. (In traditional surgery a “graft” is a piece of living tissue, organ, etc., that is transplanted.

Autografts: Skin grafts taken from the recipient. If absent or deficient of natural tissue, alternatives can be:

Cultured Sheets of epithelial cells in vitro.

Synthetic compounds (e.g., Integra—a 2 layered dermal substitute consisting superficially of silicone and deeply of bovine tendon collagen with glycosaminoglycans).

Allografts: Skin grafts taken from a donor of the same species.

Xenografts: Skin grafts taken from a donor of a different species.

Usually, good results are expected from plastic surgery that emphasizes:

Careful planning of incisions so that they fall in the line of natural skin folds or lines.

Appropriate choice of wound closure.

Use of best available suture materials.

Early removal of exposed sutures so that the wound is held closed by buried sutures.

Reconstructive plastic surgery

Reconstructive Plastic Surgery is performed to correct functional impairments caused by:

burns

traumatic injuries, such as facial bone fractures

congenital abnormalities, such as cleft lip, or cleft palate

developmental abnormalities

infection or disease

removal of cancers or tumours, such as a mastectomy for a breast cancer, a head and neck cancer and an abdominal invasion by a colon cancer

Reconstructive plastic surgery is usually performed to improve function, but it may be done to approximate a normal appearance. It is generally covered by insurance coverage but this may change according to the procedure required.

Common reconstructive surgical procedures are: breast reconstruction for women who have had a mastectomy, cleft lip and palate surgery, contracture surgery for burn survivors, creating a new outer ear when one is congenitally absent, and closing skin and mucosa defects after removal of tumors in the head and neck region.

Plastic surgeons developed the use of microsurgery to transfer tissue for coverage of a defect when no local tissue is available. tissue flaps comprised of skin, muscle, bone, fat or a combination, may be removed from the body, moved to another site on the body and reconnected to a blood supply by suturing arteries and veins as small as 1-2 mm in diameter.

Cosmetic surgery

Cosmetic Surgery defined as a subspecialty of surgery that uniquely restricts itself to the enhancement of appearance through surgical and medical techniques. It is specifically concerned with maintaining normal appearance, restoring it, or enhancing it beyond the average level toward some aesthetic ideal. In 2006, nearly 11 million cosmetic surgeries were performed in the United States alone.

It is important to distinguish the terms “plastic surgery” and “cosmetic surgery”: Plastic Surgery is a recognized surgical specialty and is defined as the subspecialty dedicated to the surgical repair of defects of form or function – this includes cosmetic (or aesthetic) surgery, as well as reconstructive surgery. The term “cosmetic surgery” however, refers to surgery that is designed to improve cosmetics alone. Many other surgical specialists are also required to learn certain cosmetic procedures during their training programs. Contributing disciplines include dermatology, general surgery, plastic surgery, otolaryngology, maxillofacial surgery, and oculoplastic surgery.

The most prevalent aesthetic/cosmetic procedures are listed below. Most of these types of surgery are more commonly known by their “common names.” These are also listed when pertinent.

Abdominal etching, or Ab etching, is used to contour and shape the abdominal fat pad to provide patients with a flat stomach.

Abdominoplasty (or “tummy tuck”): reshaping and firming of the abdomen

Blepharoplasty (or “eyelid surgery”): Reshaping of the eyelids or the application of permanent eyeliner, including Asian blepharoplasty

Mammoplasty

Breast augmentation (or “breast enlargement” or “boob job”): Augmentation of the breasts. This can involve either fat grafting, saline or silicone gel prosthetics. Initially performed to women with micromastia

Breast reduction: Removal of skin and glandular tissue. Indicated to reduce back and shoulder pain in women with gigantomastia and/or for psychological benefit in women with gigantomastia/macromastia and men with gynecomastia.

Breast lift (Mastopexy): Lifting or reshaping of breasts to make them less saggy, often after weight loss (after a pregnancy, for example). It involves removal of breast skin as opposed to glandular tissue.

Buttock Augmentation (or “butt augmentation” or “butt implants”): Enhancement of the buttocks. This procedure can be performed by using silicone implants or fat grafting and transfer from other areas of the body.

Chemical peel: Minimizing the appearance of acne, pock, and other scars as well as wrinkles (depending on concentration and type of agent used, except for deep furrows), solar lentigines (age spots, freckles), and photodamage in general. Chemical peels commonly involve carbolic acid (Phenol), trichloroacetic acid (TCA), glycolic acid (AHA), or salicylic acid (BHA) as the active agent.

Labiaplasty: Surgical reduction and reshaping of the labia

Rhinoplasty (or “nose job”): Reshaping of the nose

Otoplasty (or ear surgery): Reshaping of the ear

Rhytidectomy (or “face lift”): Removal of wrinkles and signs of aging from the face

Suction-Assisted Lipectomy (or liposuction): Removal of fat from the body

Chin augmentation: Augmentation of the chin with an implant (e.g. silicone) or by sliding genioplasty of the jawbone.

Cheek augmentation

Collagen, fat, and other tissue filler injections (e.g. hyaluronic acid)

Laser skin resurfacing

Male Pectoral Implant : It is a procedure used to enhance chest size in men by inserting silicone implants under the chest muscle.

In recent years, a growing number of patients seeking cosmetic surgery have visited other countries to find doctors with lower costs.[8] These medical tourists seek to get their procedures done for a cost savings in countries including Cuba, Thailand, Argentina, India, and some areas of eastern Europe. The risk of complications and the lack of after surgery support are often overlooked by those simply looking for the cheapest option.

Plastic surgery sub-specialities

Plastic surgery is a broad field, and may be subdivided further. Plastic surgery training and approval by the American Board of Plastic Surgery includes mastery of the following as well:

Craniofacial surgery is generally divided into pediatric and adult craniofacial surgery. Pediatric craniofacial surgery mostly revolves around the treatment of congenital anomalies of the craniofacial skeleton and soft tissues, such as cleft lip and palate, craniosynostosis, and pediatric fractures. Because these children have multiple issues, the best approach to providing care to them is an interdisciplinary approach which also includes otolaryngologists, speech therapists, occupational therapists and geneticists. Adult craniofacial surgery deals mostly with fractures and secondary surgeries (such as orbital reconstruction). Both subspecialities usually require advanced training in craniofacial surgery. The craniofacial surgery field is also practiced by maxillofacial surgeons (see craniofacial surgery).

Hand surgery is concerned with acute injuries and chronic diseases of the hand and wrist, correction of congenital malformations of the upper extremities, and peripheral nerve problems (such as brachial plexus injuries or carpal tunnel syndrome). Hand surgery is an important part of training in plastic surgery, as well as microsurgery, which is necessary to replant an amputated extremity. Most Hand surgeons will opt to complete a fellowship in Hand Surgery. The Hand surgery field is also practiced by orthopedic surgeons and general surgeons (see Hand surgeon).

Microsurgery is generally concerned with the reconstruction of missing tissues by transferring a piece of tissue to the reconstruction site and reconnecting blood vessels. Popular subspecialty areas are breast reconstruction, head and neck reconstruction, hand surgery/replantation, and brachial plexus surgery.

Burn surgery

Aesthetic or cosmetic surgery is concerned with the correction of form and aging. Plastic surgeons usually excel in this field because of their thorough knowledge of anatomy and extensive experience with reconstruction and congenital anomalies correction. Popular operations include amongst other breast augmentation, rhinoplasty, face lift, liposuction and mastopexy.

Pediatric plastic surgery. Children often face medical issues unique from the experiences of an adult patient. Many birth defects or syndromes present at birth are best treated in childhood, and pediatric plastic surgeons specialize in treating these conditions in children. Conditions commonly treated by pediatric plastic surgeons include craniofacial anomalies, cleft lip and palate and congenital hand deformities.

Although not a traditionally recognized plastic surgery subspecialty, facial plastic and reconstructive surgery is concerned with the aesthetic and reconstructive problems in the head and neck region. Facial plastic surgeons have extensive experience in the head and neck surgery after completing a five year otolaryngology residency, and subsequently one-year facial plastic and reconstructive surgery fellowship. However, facial plastic surgeons are not plastic surgeons in that their training does not encompass 3-7 years of general surgery training and 2-4 years of comprehensive plastic surgery training. Facial plastic

surgeons commonly performed procedure such as rhytidectomy, rhinoplasty, blepharoplasty, brow lifting, and skin cancer reconstruction.

Same-sex relationship

A Same-sex relationship can take one of several forms, from romantic and sexual, to non-romantic close relationships between two persons of the same sex.

The term same-sex relationship may be used when the sexual orientation of participants in a same-sex relationship is not known. As bisexual or pansexual people may participate in same-sex relationships, some activists claim that referring to a same-sex relationship as a “gay relationship” or a “lesbian relationship” is a form of bisexual erasure. The term same-sex marriage is used similarly.

Continue reading

It is my duty to assess behaviors for their impact on health and wellbeing. When something is beneficial, such as exercise, good nutrition, or adequate sleep, it is my duty to recommend it. Likewise, when something is harmful, such as smoking, overeating, alcohol or drug abuse, and homosexual sex, it is my duty to discourage it.

Notice to Reader:

“The Boards of both CERC Canada and CERC USA are aware that the topic of homosexuality is a controversial one that deeply affects the personal lives of many North Americans. Both Boards strongly reiterate the Catechism’s teaching that people who self-identify as gays and lesbians must be treated with ‘respect, compassion, and sensitivity’ (CCC #2358). The Boards also support the Church’s right to speak to aspects of this issue in accordance with her own self-understanding. Articles in this section have been chosen to cast light on how the teachings of the Church intersect with the various social, moral, and legal developments in secular society. CERC will not publish articles which, in the opinion of the editor, expose gays and lesbians to hatred or intolerance.”

Executive Summary

Levels of Promiscuity

Physical Health

Mental Health

Life Span

Monogamy

The Health Risks of Gay Sex

Introduction

I. Differences between homosexual and heterosexual relationships

A. Promiscuity

B. Physical health

1. Male Homosexual Behavior

a. Anal-genital

b. Oral-anal

c. Human Waste

d. Fisting

e. Sadism

f. Conclusion

2. Female Homosexual Behavior

C. Mental health

1. Psychiatric Illness

2. Reckless Sexual Behavior

D. Life span

E. Definition of “monogamy”

II. Cultural Implications of Promiscuity

Conclusion

Appendix A

Definitional Impediments to Research

Endnotes

Executive Summary

Sexual relationships between members of the same sex expose gays, lesbians and bisexuals to extreme risks of Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs), physical injuries, mental disorders and even a shortened life span. There are five major distinctions between gay and heterosexual relationships, with specific medical consequences. They are:

•Levels of Promiscuity

Prior to the AIDS epidemic, a 1978 study found that 75 percent of white, gay males claimed to have had more than 100 lifetime male sex partners: 15 percent claimed 100-249 sex partners; 17 percent claimed 250-499; 15 percent claimed 500- 999; and 28 percent claimed more than 1,000 lifetime male sex partners. Levels of promiscuity subsequently declined, but some observers are concerned that promiscuity is again approaching the levels of the 1970s. The medical consequence of this promiscuity is that gays have a greatly increased likelihood of contracting HIV/AIDS, syphilis and other STDs.

Similar extremes of promiscuity have not been documented among lesbians. However, an Australian study found that 93 percent of lesbians reported having had sex with men, and lesbians were 4.5 times more likely than heterosexual women to have had more than 50 lifetime male sex partners. Any degree of sexual promiscuity carries the risk of contracting STDs.

•Physical Health

Common sexual practices among gay men lead to numerous STDs and physical injuries, some of which are virtually unknown in the heterosexual population. Lesbians are also at higher risk for STDs. In addition to diseases that may be transmitted during lesbian sex, a study at an Australian STD clinic found that lesbians were three to four times more likely than heterosexual women to have sex with men who were high-risk for HIV.

•Mental Health

It is well established that there are high rates of psychiatric illnesses, including depression, drug abuse, and suicide attempts, among gays and lesbians. This is true even in the Netherlands, where gay, lesbian and bisexual (GLB) relationships are far more socially acceptable than in the U.S. Depression and drug abuse are strongly associated with risky sexual practices that lead to serious medical problems.

•Life Span

The only epidemiological study to date on the life span of gay men concluded that gay and bisexual men lose up to 20 years of life expectancy.

•Monogamy

Monogamy, meaning long-term sexual fidelity, is rare in GLB relationships, particularly among gay men. One study reported that 66 percent of gay couples reported sex outside the relationship within the first year, and nearly 90 percent if the relationship lasted five years.

Encouraging people to engage in risky sexual behavior undermines good health and can result in a shortened life span. Yet that is exactly what employers and governmental entities are doing when they grant GLB couples benefits or status that make GLB relationships appear more socially acceptable.

The Health Risks of Gay Sex

Introduction

In the early 1980s, while working at Beth Israel Hospital, I vividly remember seeing healthy young gay men dying of a mysterious disease that researchers only later identified as a sexually transmitted disease — AIDS. Over the years, I’ve seen many patients with that diagnosis die.

As a physician, it is my duty to assess behaviors for their impact on health and wellbeing. When something is beneficial, such as exercise, good nutrition, or adequate sleep, it is my duty to recommend it. Likewise, when something is harmful, such as smoking, overeating, alcohol or drug abuse, it is my duty to discourage it.

When sexual activity is practiced outside of marriage, the consequences can be quite serious. Without question, sexual promiscuity frequently spreads diseases, from trivial to serious to deadly. In fact, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 65 million Americans have an incurable sexually transmitted disease (STD).1

There are differences between men and women in the consequences of same-sex activity. But most importantly, the consequences of homosexual activity are distinct from the consequences of heterosexual activity. As a physician, it is my duty to inform patients of the health risks of gay sex, and to discourage them from indulging in harmful behavior.

I. DIFFERENCES BETWEEN HOMOSEXUAL AND HETEROSEXUAL RELATIONSHIPS

The current media portrayal of gay and lesbian relationships is that they are as healthy, stable and loving as heterosexual marriages — or even more so.2 Medical associations are promoting somewhat similar messages.3 Nevertheless, there are at least five major areas of differences between gay and heterosexual relationships, each with specific medical consequences. Those differences include:

A. Levels of promiscuity

B. Physical health

C. Mental health

D. Life span

E. Definition of “monogamy”

A. Promiscuity

Gay author Gabriel Rotello notes the perspective of many gays that “Gay liberation was founded . . . on a ‘sexual brotherhood of promiscuity,’ and any abandonment of that promiscuity would amount to a ‘communal betrayal of gargantuan proportions.'”4 Rotello’s perception of gay promiscuity, which he criticizes, is consistent with survey results. A far-ranging study of homosexual men published in 1978 revealed that 75 percent of self-identified, white, gay men admitted to having sex with more than 100 different males in their lifetime: 15 percent claimed 100-249 sex partners; 17 percent claimed 250- 499; 15 percent claimed 500-999; and 28 percent claimed more than 1,000 lifetime male sex partners.5By 1984, after the AIDS epidemic had taken hold, homosexual men were reportedly curtailing promiscuity, but not by much. Instead of more than 6 partners per month in 1982, the average non-monogamous respondent in San Francisco reported having about 4 partners per month in 1984.6

In more recent years, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control has reported an upswing in promiscuity, at least among young homosexual men in San Francisco. From 1994 to 1997, the percentage of homosexual men reporting multiple partners and unprotected anal sex rose from 23.6 percent to 33.3 percent, with the largest increase among men under 25.7 Despite its continuing incurability, AIDS no longer seems to deter individuals from engaging in promiscuous gay sex.8

The data relating to gay promiscuity were obtained from self-identified gay men. Some advocates argue that the average would be lower if closeted homosexuals were included in the statistics.9 That is likely true, according to data obtained in a 2000 survey in Australia that tracked whether men who had sex with men were associated with the gay community. Men who were associated with the gay community were nearly four times as likely to have had more than 50 sex partners in the six months preceding the survey as men who were not associated with the gay community.10 This may imply that it is riskier to be “out” than “closeted.” Adopting a gay identity may create more pressure to be promiscuous and to be so with a cohort of other more promiscuous partners.

Excessive sexual promiscuity results in serious medical consequences — indeed, it is a recipe for transmitting disease and generating an epidemic.11 The HIV/AIDS epidemic has remained a predominantly gay issue in the U.S. primarily because of the greater degree of promiscuity among gays.12 A study based upon statistics from 1986 through 1990 estimated that 20-year-old gay men had a 50 percent chance of becoming HIV positive by age 55.13 As of June 2001, nearly 64 percent of men with AIDS were men who have had sex with men.14 Syphilis is also more common among gay men. The San Francisco Public Health Department recently reported that syphilis among the city’s gay and bisexual men was at epidemic levels. According to the San Francisco Chronicle:

“Experts believe syphilis is on the rise among gay and bisexual men because they are engaging in unprotected sex with multiple partners, many of whom they met in anonymous situations such as sex clubs, adult bookstores, meetings through the Internet and in bathhouses. The new data will show that in the 93 cases involving gay and bisexual men this year, the group reported having 1,225 sexual partners.”15

A study done in Baltimore and reported in the Archives of Internal Medicine found that gay men contracted syphilis at three to four times the rate of heterosexuals.16 Promiscuity is the factor most responsible for the extreme rates of these and other Sexually Transmitted Diseases cited below, many of which result in a shortened life span for men who have sex with men.

Promiscuity among lesbians is less extreme, but it is still higher than among heterosexual women. Overall, women tend to have fewer sex partners than men. But there is a surprising finding about lesbian promiscuity in the literature. Australian investigators reported that lesbian women were 4.5 times more likely to have had more than 50 lifetime male partners than heterosexual women (9 percent of lesbians versus 2 percent of heterosexual women); and 93 percent of women who identified themselves as lesbian reported a history of sex with men.17 Other studies similarly show that 75-90 percent of women who have sex with women have also had sex with men.18

B. Physical Health

Unhealthy sexual behaviors occur among both heterosexuals and homosexuals. Yet the medical and social science evidence indicate that homosexual behavior is uniformly unhealthy. Although both male and female homosexual practices lead to increases in Sexually Transmitted Diseases, the practices and diseases are sufficiently different that they merit separate discussion.

1. Male Homosexual Behavior

Men having sex with other men leads to greater health risks than men having sex with women19 not only because of promiscuity but also because of the nature of sex among men. A British researcher summarizes the danger as follows:

“Male homosexual behaviour is not simply either ‘active’ or ‘passive,’ since penile-anal, mouth-penile, and hand-anal sexual contact is usual for both partners, and mouth-anal contact is not infrequent. . . . Mouth-anal contact is the reason for the relatively high incidence of diseases caused by bowel pathogens in male homosexuals. Trauma may encourage the entry of micro-organisms and thus lead to primary syphilitic lesions occurring in the anogenital area. . . . In addition to sodomy, trauma may be caused by foreign bodies, including stimulators of various kinds, penile adornments, and prostheses.”20

Although the specific activities addressed below may be practiced by heterosexuals at times, homosexual men engage in these activities to a far greater extent.21

a. Anal-genital

Anal intercourse is the sine qua non of sex for many gay men.22 Yet human physiology makes it clear that the body was not designed to accommodate this activity. The rectum is significantly different from the vagina with regard to suitability for penetration by a penis. The vagina has natural lubricants and is supported by a network of muscles. It is composed of a mucus membrane with a multi-layer stratified squamous epithelium that allows it to endure friction without damage and to resist the immunological actions caused by semen and sperm. In comparison, the anus is a delicate mechanism of small muscles that comprise an “exit-only” passage. With repeated trauma, friction and stretching, the sphincter loses its tone and its ability to maintain a tight seal. Consequently, anal intercourse leads to leakage of fecal material that can easily become chronic.

The potential for injury is exacerbated by the fact that the intestine has only a single layer of cells separating it from highly vascular tissue, that is, blood. Therefore, any organisms that are introduced into the rectum have a much easier time establishing a foothold for infection than they would in a vagina. The single layer tissue cannot withstand the friction associated with penile penetration, resulting in traumas that expose both participants to blood, organisms in feces, and a mixing of bodily fluids.

Furthermore, ejaculate has components that are immunosuppressive. In the course of ordinary reproductive physiology, this allows the sperm to evade the immune defenses of the female. Rectal insemination of rabbits has shown that sperm impaired the immune defenses of the recipient.23 Semen may have a similar impact on humans.24

The end result is that the fragility of the anus and rectum, along with the immunosuppressive effect of ejaculate, make anal-genital intercourse a most efficient manner of transmitting HIV and other infections. The list of diseases found with extraordinary frequency among male homosexual practitioners as a result of anal intercourse is alarming:

Anal Cancer

Chlamydia trachomatis

Cryptosporidium

Giardia lamblia

Herpes simplex virus

Human immunodeficiency virus

Human papilloma virus

Isospora belli

Microsporidia

Gonorrhea

Viral hepatitis types B & C

Syphilis25

Sexual transmission of some of these diseases is so rare in the exclusively heterosexual population as to be virtually unknown. Others, while found among heterosexual and homosexual practitioners, are clearly predominated by those involved in homosexual activity. Syphilis, for example is found among heterosexual and homosexual practitioners. But in 1999, King County, Washington (Seattle), reported that 85 percent of syphilis cases were among self-identified homosexual practitioners.26 And as noted above, syphilis among homosexual men is now at epidemic levels in San Francisco.27

A 1988 CDC survey identified 21 percent of all Hepatitis B cases as being homosexually transmitted while 18 percent were heterosexually transmitted.28 Since homosexuals comprise such a small percent of the population (only 1-3 percent),29 they have a significantly higher rate of infection than heterosexuals.30

Anal intercourse also puts men at significant risk for anal cancer. Anal cancer is the result of infection with some subtypes of human papilloma virus (HPV), which are known viral carcinogens. Data as of 1989 showed the rates of anal cancer in male homosexual practitioners to be 10 times that of heterosexual males, and growing. 30 Thus, the prevalence of anal cancer among gay men is of great concern. For those with AIDS, the rates are doubled.31

Other physical problems associated with anal intercourse are:

hemorrhoids

anal fissures

anorectal trauma

retained foreign bodies.32

b. Oral-anal

There is an extremely high rate of parasitic and other intestinal infections documented among male homosexual practitioners because of oral-anal contact. In fact, there are so many infections that a syndrome called “the Gay Bowel” is described in the medical literature.33 “Gay bowel syndrome constitutes a group of conditions that occur among persons who practice unprotected anal intercourse, anilingus, or fellatio following anal intercourse.”34 Although some women have been diagnosed with some of the gastrointestinal infections associated with “gay bowel,” the vast preponderance of patients with these conditions are men who have sex with men.35

“Rimming” is the street name given to oralanal contact. It is because of this practice that intestinal parasites ordinarily found in the tropics are encountered in the bodies of American gay men. Combined with anal intercourse and other homosexual practices, “rimming” provides a rich opportunity for a variety of infections.

Men who have sex with men account for the lion’s share of the increasing number of cases in America of sexually transmitted infections that are not generally spread through sexual contact. These diseases, with consequences that range from severe and even life-threatening to mere annoyances, include Hepatitis A,36 Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica,37 Epstein-Barr virus,38 Neisseria meningitides,39 Shigellosis, Salmonellosis, Pediculosis, scabies and Campylobacter.40 The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) identified a 1991 outbreak of Hepatitis A in New York City, in which 78 percent of male respondents identified themselves as homosexual or bisexual.41While Hepatitis A can be transmitted by routes other than sexual, a preponderance of Hepatitis A is found in gay men in multiple states.42 Salmonella is rarely associated with sexual activity except among gay men who have oral-anal and oral-genital contact following anal intercourse.43 The most unsettling new discovery is the reported sexual transmission of typhoid. This water-borne disease, well known in the tropics, only infects 400 people each year in the United States, usually as a result of ingestion of contaminated food or water while abroad. But sexual transmission was diagnosed in Ohio in a series of male sex partners of one male who had traveled to Puerto Rico.44

In America, Human Herpes Virus 8 (called Herpes Type 8 or HHV-8) is a disease found exclusively among male homosexual practitioners. Researchers have long noted that men who contracted AIDS through homosexual behavior frequently developed a previously rare form of cancer called Kaposi’s sarcoma. Men who contract HIV/AIDS through heterosexual sex or intravenous drug use rarely display this cancer. Recent studies confirm that Kaposi’s sarcoma results from infection with HHV-8. The New England Journal of Medicine described one cohort in San Francisco where 38 percent of the men who admitted any homosexual contact within the previous five years tested positive for this virus while none of the exclusively heterosexual men tested positive. The study predicted that half of the men with both HIV and HHV-8 would develop the cancer within 10 years.45 The medical literature is currently unclear as to the precise types of sexual behavior that transmit HHV-8, but there is a suspicion that it may be transmitted via saliva.46

c. Human Waste

Some gay men sexualize human waste, including the medically dangerous practice of coprophilia, which means sexual contact with highly infectious fecal wastes.47 This practice exposes the participants to all of the risks of anal-oral contact and many of the risks of analgenital contact.

d. Fisting

“Fisting” refers to the insertion of a hand or forearm into the rectum, and is far more damaging than anal intercourse. Tears can occur, along with incompetence of the anal sphincter. The result can include infections, inflammation and, consequently, enhanced susceptibility to future STDs. Twenty-two percent of homosexuals in one survey admitted to having participated in this practice.48

e. Sadism

The sexualization of pain and cruelty is described as sadism, named for the 18th Century novelist, the Marquis de Sade. His novel Justine describes repeated rapes and non-consensual whippings.49 Not all persons who practice sadism engage in the same activities. But a recent advertisement for a sadistic “conference” included a warning that participants might see “intentional infliction of pain [and] cutting of the skin with bleeding . . . .” Scheduled workshops included “Vaginal Fisting” (with a demonstration), “Sacred Sexuality and Cutting” with “a demonstration of a cutting with a live subject,” “Rough Rope,” and a “Body Harness” workshop that was to involve “demonstrating and coaching the tying of erotic body harnesses that involve the genitals, male and female.”50 A similar event entitled the “Vicious Valentine” occurred near Chicago on Feb. 15-17, 2002.51 The medical consequences of such activities range from mild to fatal, depending upon the nature of the injuries inflicted.52 As many as 37 percent of homosexuals have practiced some form of sadism.53

f. Conclusion

The consequences of homosexual activity have significantly altered the delivery of medical care to the population at-large. With the increased incidence of STD organisms in unexpected places, simple sore throat is no longer so simple. Doctors must now ask probing questions of their patients or risk making a misdiagnosis. The evaluation of a sore throat must now include questions about oral and anal sex. A case of hemorrhoids is no longer just a surgical problem. We must now inquire as to sexual practice and consider that anal cancer, rectal gonorrhea, or rectal chlamydia may be secreted in what deceptively appears to be “just hemorrhoids.”54 Moreover, data shows that rectal and throat gonorrhea, for example, are without symptoms in 75 percent of cases.55

The impact of the health consequences of gay sex is not confined to homosexual practitioners. Even though nearly 11 million people in America are directly affected by cancer, compared to slightly more than three-quarters of a million with AIDS,56 AIDS spending per patient is more than seven times that for cancer.57 The inequity for diabetes and heart disease is even more striking.58 Consequently, the disproportionate amount of money spent on AIDS detracts from research into cures for diseases that affect more people.

2. Female Homosexual Behavior

Lesbians are also at higher risk for STDs and other health problems than heterosexuals.59 However, the health consequences of lesbianism are less well documented than for male homosexuals. This is partly because the devastation of AIDS has caused male homosexual activity to draw the lion’s share of medical attention. But it is also because there are fewer lesbians than gay men,60 and there is no evidence that lesbians practice the same extremes of same-sex promiscuity as gay men. The lesser amount of medical data does not mean, however, that female homosexual behavior is without recognized pathology. Much of the pathology is associated with heterosexual activity by lesbians.

Among the difficulties in establishing the pathologies associated with lesbianism is the problem of defining who is a lesbian.61 Study after study documents that the overwhelming majority of self-described lesbians have had sex with men.62 Australian researchers at an STD clinic found that only 7 percent of their lesbian sample had never had sexual contact with a male.63

Not only did lesbians commonly have sex with men, but with lots of men. They were 4.5 times as likely as exclusively heterosexual controls to have had more than 50 lifetime male sex partners.64 Consequently, the lesbians’ median number of male partners was twice that of exclusively heterosexual women.65 Lesbians were three to four times more likely than heterosexual women to have sex with men who were high-risk for HIV disease-homosexual, bisexual, or IV drug-abusing men.66 The study “demonstrates that WSW [women who have sex with women] are more likely than non- WSW to engage in recognized HIV risk behaviours such as IDU [intravenous drug use], sex work, sex with a bisexual man, and sex with a man who injects drugs, confirming previous reports.”67

Bacterial vaginosis, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, heavy cigarette smoking, alcohol abuse, intravenous drug use, and prostitution were present in much higher proportions among female homosexual practitioners.68 Intravenous drug abuse was nearly six times as common in this group.69In one study of women who had sex only with women in the prior 12 months, 30 percent had bacterial vaginosis.70 Bacterial vaginosis is associated with higher risk for pelvic inflammatory disease and other sexually transmitted infections.71

In view of the record of lesbians having sex with many men, including gay men, and the increased incidence of intravenous drug use among lesbians, lesbians are not low risk for disease. Although researchers have only recently begun studying the transmission of STDs among lesbians, diseases such as “crabs,” genital warts, chlamydia and herpes have been reported.72 Even women who have never had sex with men have been found to have HPV, trichomoniasis and anogenital warts.73

C. Mental Health

1. Psychiatric Illness

Multiple studies have identified high rates of psychiatric illness, including depression, drug abuse and suicide attempts, among selfprofessed gays and lesbians.74 Some proponents of GLB rights have used these findings to conclude that mental illness is induced by other people’s unwillingness to accept same-sex attraction and behavior as normal. They point to homophobia, effectively defined as any opposition to or critique of gay sex, as the cause for the higher rates of psychiatric illness, especially among gay youth.75 Although homophobia must be considered as a potential cause for the increase in mental health problems, the medical literature suggests other conclusions.

An extensive study in the Netherlands undermines the assumption that homophobia is the cause of increased psychiatric illness among gays and lesbians. The Dutch have been considerably more accepting of same-sex relationships than other Western countries — in fact, same-sex couples now have the legal right to marry in the Netherlands.76 So a high rate of psychiatric disease associated with homosexual behavior in the Netherlands means that the psychiatric disease cannot so easily be attributed to social rejection and homophobia.

The Dutch study, published in the Archives of General Psychiatry, did indeed find a high rate of psychiatric disease associated with same-sex sex.77 Compared to controls who had no homosexual experience in the 12 months prior to the interview, males who had any homosexual contact within that time period were much more likely to experience major depression, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia and obsessive compulsive disorder. Females with any homosexual contact within the previous 12 months were more often diagnosed with major depression, social phobia or alcohol dependence. In fact, those with a history of homosexual contact had higher rates of nearly all psychiatric pathologies measured in the study.78 The researchers found “that homosexuality is not only associated with mental health problems during adolescence and early adulthood, as has been suggested, but also in later life.”79 Researchers actually fear that methodological features of “the study might underestimate the differences between homosexual and heterosexual people.”80

The Dutch researchers concluded, “this study offers evidence that homosexuality is associated with a higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders. The outcomes are in line with findings from earlier studies in which less rigorous designs have been employed.”81 The researchers offered no opinion as to whether homosexual behavior causes psychiatric disorders, or whether it is the result of psychiatric disorders.

2. Reckless Sexual Behavior

Depression and drug abuse can lead to reckless sexual behavior, even among those who are most likely to understand the deadly risks. In an article that was part of a series on “AIDS at 20,” the New York Times reported the risks that many gay men take. One night when a gay HIV prevention educator named Seth Watkins got depressed, he met an attractive stranger, had anal intercourse without a condom — and became HIV positive. In spite of his job training, the HIV educator nevertheless employed the psychological defense of “denial” in explaining his own sexual behavior:

“[L]ike an increasing number of gay men in San Francisco and elsewhere, Mr. Watkins sometimes still puts himself and possibly other people at risk. ‘I don’t like to think about it because I don’t want to give anyone H.I.V.,’ Mr. Watkins said.”82

Another gay man named Vince, who had never before had anal intercourse without a condom, went to a sex club on the spur of the moment when he got depressed, and had unprotected sex:

“I was definitely in a period of depression . . . . And there was just something about that particular circumstance and that particular person. I don’t know how to describe it. It just appealed to me; it made it seem like it was all right.”83

Some of the men interviewed by the New York Times are deliberately reckless. One fatalistic gay man with HIV makes no apology for putting other men at risk:

“The prospect of going through the rest of your life having to cover yourself up every time you want to get intimate with someone is an awful one. . . . Now I’ve got H.I.V. and I don’t have to worry about getting it,” he said. “There is a part of me that’s relieved. I was tired of always having to be careful, of this constant diligence that has to be paid to intimacy when intimacy should be spontaneous.”84

After admitting to almost never using condoms he adds:

“There is no such thing as safe sex. . . . If people want to use condoms, they can. I didn’t go out and purposely get H.I.V. Accidents happen.”85

Other reports show similar disregard for the safety of self and others. A1998 study in Seattle found that 10 percent of HIV-positive men admitted they engaged in unprotected anal sex, and the percentage doubled in 2000.86 According to a study of men who attend gay “circuit” parties,87 the danger at such events is even greater. Ten percent of the men surveyed expected to become HIV-positive in their lifetime. Researchers discovered that 17 percent of the circuit party attendees surveyed were already HIV positive.88 Two thirds of those attending circuit parties had oral or anal sex, and 28 percent did not use condoms.89

In addition, drug use at circuit parties is ubiquitous. Although only 57 percent admit going to circuit parties to use drugs, 95 percent of the survey participants said they used psychoactive drugs at the most recent event they attended.90 There was a direct correlation between the number of drugs used during a circuit party weekend and the likelihood of unprotected anal sex.91 The researchers concluded that in view of their findings, “the likelihood of transmission of HIV and other Sexually Transmitted Diseases among party attendees and secondary partners becomes a real public health concern.”92

Good mental health would dictate foregoing circuit parties and other risky sex. But neither education nor adequate access to health care is a deterrent to such reckless behavior. “Research at the University of New South Wales found well-educated professional men in early middle age — those who experienced the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s — are most likely not to use a condom.”93

D. Shortened Life Span

The greater incidence of physical and mental health problems among gays and lesbians has serious consequences for length of life. While many are aware of the death toll from AIDS, there has been little public attention given to the magnitude of the lost years of life.

An epidemiological study from Vancouver, Canada of data tabulated between 1987 and 1992 for AIDS-related deaths reveals that male homosexual or bisexual practitioners lost up to 20 years of life expectancy. The study concluded that if 3 percent of the population studied were gay or bisexual, the probability of a 20-year-old gay or bisexual man living to 65 years was only 32 percent, compared to 78 percent for men in general.94 The damaging effects of cigarette smoking pale in comparison -cigarette smokers lose on average about 13.5 years of life expectancy.95

The impact on length of life may be even greater than reported in the Canadian study. First, HIV/AIDS is underreported by as much as 15-20 percent, so it is likely that not all AIDSrelated deaths were accounted for in the study.96 Second, there are additional major causes of death related to gay sex. For example, suicide rates among a San Francisco cohort were 3.4 times higher than the general U.S. male population in 1987.97 Other potentially fatal ailments such as syphilis, anal cancer, and Hepatitis B and C also affect gay and bisexual men disproportionately.98

E. “Monogamy”

Monogamy for heterosexual couples means at a minimum sexual fidelity. The most extensive survey of sex in America found that “a vast majority [of heterosexual married couples] are faithful while the marriage is intact.”99 The survey further found that 94 percent of married people and 75 percent of cohabiting people had only one partner in the prior year.100 In contrast, long-term sexual fidelity is rare among GLB couples, particularly among gay males. Even during the coupling period, many gay men do not expect monogamy. A lesbian critic of gay males notes that:

“After a period of optimism about the longrange potential of gay men’s one-on-one relationships, gay magazines are starting to acknowledge the more relaxed standards operating here, with recent articles celebrating the bigger bang of sex with strangers or proposing ‘monogamy without fidelity’-the latest Orwellian formulation to excuse having your cake and eating it too.”101

Gay men’s sexual practices appear to be consistent with the concept of “monogamy without fidelity.” Astudy of gay men attending circuit parties showed that 46 percent were coupled, that is, they claimed to have a “primary partner.” Twenty-seven percent of the men with primary partners “had multiple sex partners (oral or anal) during their most recent circuit party weekend . . . .”102 For gay men, sex outside the primary relationship is ubiquitous even during the first year. Gay men reportedly have sex with someone other than their partner in 66 percent of relationships within the first year, rising to approximately 90 percent if the relationship endures over five years.103 And the average gay or lesbian relationship is short lived. In one study, only 15 percent of gay men and 17.3 percent of lesbians had relationships that lasted more than three years.104 Thus, the studies reflect very little long-term monogamy in GLB relationships.

II. CULTURAL IMPLICATIONS OF PROMISCUITY

“Don’t tear down a fence until you know why it was put up.” ~ African proverb

The societal implications of the unrestrained sexual activity described above are devastating. The ideal of sexual activity being limited to marriage, always defined as male-female, has been a fence erected in all civilizations around the globe.105 Throughout history, many people have climbed over the fence, engaging in premarital, extramarital and homosexual sex. Still, the fence stands; the limits are visible to all. Climbing over the fence, metaphorically, has always been recognized as a breach of those limits, even by the breachers themselves. No civilization can retain its vitality for multiple generations after removing the fence.106

But now social activists are saying that there should be no fence, and that to destroy the fence is an act of liberation.107 If the fence is torn down, there is no visible boundary to sexual expression. If gay sex is socially acceptable, what logical reason can there be to deny social acceptance of adultery, polygamy, or pedophilia? The polygamist movement already has support from some of the advocates for GLB rights.108 And some in the psychological profession are floating the idea that maybe pedophilia is not so damaging to children after all.109

Lesbian social critic Camille Paglia observes, “history shows that male homosexuality, which like prostitution flourishes with urbanization and soon becomes predictably ritualized, always tends toward decadence.”110 Gay author Gabriel Rotello writes of the changes in homosexual behavior in the last century:

“Most accounts of male-on-male sex from the early decades of this century [20th] cite oral sex, and less often masturbation, as the predominant forms of activity, with the acknowledged homosexual fellating or masturbating his partner. Comparatively fewer accounts refer to anal sex. My own informal survey of older gay men who were sexually active prior to World War II gives credence to the idea that anal sex, especially anal sex with multiple partners, was considerably less common than it later became.”111

Not only has the practice of anal sex increased, condom use has declined 20 percent and multi-partner sex has doubled in the last seven years,112 despite billions of dollars spent on HIV prevention campaigns. “In many cases, the prevention slogans that galvanized gay men in the early years of the epidemic now fall on deaf ears.”113 As should be expected, the health-care costs resulting from gay promiscuity are substantial.114

Social approval of gay sex leads to an increase in such behavior. As early as 1993, Newsweek reported that the growing media presence and social acceptance of homosexual behavior was leading to teenager experimentation to the extent that it was “becoming chic.”115 A more recent report stated that “the way gays and lesbians appear in the media may make some people more comfortable acting on homosexual impulses.”116 In addition, one of the goals of GLB advocates’ quest for domestic partner benefits from employers is to motivate more gays and lesbians “to come out of the closet.”117 If, as suggested above, being “out” results in a greater incidence of promiscuity, employer decisions to provide domestic partner benefits may have a negative impact on employee health. Indeed, giving gays and lesbians the social approval they desire may ultimately lead to an early death for employees who otherwise might have restrained their sexual behavior.

Research designed to prove that gays and lesbians are “born that way” has come up empty — there is no scientific evidence that being gay or lesbian is genetically determined.118 Even researcher Dean Hamer, who once hoped he had identified a “gay gene,” admits “there is a lot more than just genes going on.”119

CONCLUSION

It is clear that there are serious medical consequences to same-sex behavior. Identification with a GLB community appears to lead to an increase in promiscuity, which in turn leads to a myriad of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and even early death. A compassionate response to requests for social approval and recognition of GLB relationships is not to assure gays and lesbians that homosexual relationships are just like heterosexual ones, but to point out the health risks of gay sex and promiscuity. Approving same-sex relationships is detrimental to employers, employees and society in general.

APPENDIX A

Definitional Impediments to Research

Unfortunately, endeavors to assess the actual practices and the health consequences of male and female homosexual behavior are hampered by imprecise definitions. For many, being gay or lesbian or bisexual is a political identity that does not necessarily correspond to sexual behavior. And investigators find that sexual behavior fluctuates over time:

“[P]eople often change their sexual behavior during their lifetimes, making it impossible to state that a particular set of behaviors defines a person as gay. A man who has sex with men today, for example, might not have done so 10 years ago.”120

Defining the terms becomes even more difficult when people who identify as gay or lesbian enter heterosexual relationships. Joanne Loulan, a well-known lesbian, has talked openly about her two-year relationship with a man: “‘I come from this background that sex is an activity, it’s not an identity,’ says Loulan. ‘It was funny for a while, but then it turned out to be something more connected, more deep. Something more important. And that’s when my life started really going topsy turvy.'” While critics complain that “You can’t be a lesbian and be having sex with men,” Loulan sees no contradiction in the fact that she “adamantly refuses to call herself a bisexual, to give up the lesbian identity.”121

Several high-profile lesbian media stars that have abandoned lesbianism further illustrate the difficulty in defining homosexuality. An article about the now defunct couple, Anne Heche and Ellen Degeneres, said, “Although the pair never publicly discussed the reason for their breakup, it has been heavily rumored that Heche decided to go back to heterosexuality.”122 Heche married a man on Sept. 1, 2001.123

As recently as June 2000, pop-music star Sinead O’Connor said, “I’m a lesbian . . . although I haven’t been very open about that, and throughout most of my life I’ve gone out with blokes because I haven’t necessarily been terribly comfortable about being a lesbian. But I actually am a lesbian.”124 Then, shocking the gay world that applauded her “coming out,” O’Connor’s sexual identity fluctuated again when she withdrew from participating in a lesbian music festival because of her marriage to British Press Association reporter Nick Sommerlad.125

Although women get most of the press coverage of fluctuating between same-sex and heterosexual relationships, men can experience similar fluidity. Gay author John Stoltenberg has lived with a lesbian, Andrea Dworkin, since 1974.126 And a 2000 survey in Australia found that 19 percent of gay men reported having sex with a woman in the six months prior to the survey.127 This fluctuation in sexual “orientation” inhibits the creation of a fixed definition of homosexuality. As one group of researchers stated the problem:

“Does a man who has homosexual sex in prison count as a homosexual? Does a man who left his wife of twenty years for a gay lover count as a homosexual or heterosexual? Do you count the number of years he spent with his wife as compared to his lover? Does the married woman who had sex with her college roommate a decade ago count? Do you assume that one homosexual experience defines someone as gay for all time?”128

Despite the difficulty in defining homosexuality, the one thing that is clear is that those who engage in same-sex practices or identify themselves as gay, lesbian or bisexual constitute a very small percentage of the population. The most reliable studies indicate that 1-3 percent of people — and probably less than 2 percent — consider themselves to be gay, lesbian or bisexual, or currently practice same-sex sex.129

Endnotes

1.”Tracking the Hidden Epidemics: Trends in STDs in the United States, 2000,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), available at www.cdc.gov.

2.Becky Birtha, “Gay Parents and the Adoption Option,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, March 04, 2002, www.philly.com/mld/inquirer/news/editorial/ 2787531.htm; Grant Pick, “Make Room for Daddy — and Poppa,” The Chicago Tribune Internet Edition, March 24, 2002, www.chicagotribune.com/features/magazine/chi– 0203240463mar24.story

3.Ellen C. Perrin, et al., “Technical Report: Coparent or Second-Parent Adoption by Same-Sex Parents,” Pediatrics, 109(2): 341-344 (2002).

4.Gabriel Rotello, Sexual Ecology: AIDS and the Destiny of Gay Men, p. 112, New York: Penguin Group, 1998 (quoting gay writer Michael Lynch).

5.Alan P. Bell and Martin S. Weinberg, Homosexualities: A study of Diversity Among Men and Women, p. 308, Table 7, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978.

6.Leon McKusick, et al., “Reported Changes in the Sexual Behavior of Men at Risk for AIDS, San Francisco, 1982-84 — the AIDS Behavioral Research Project,” Public Health Reports, 100(6): 622-629, p. 625, Table 1 (November- December 1985). In 1982 respondents reported an average of 4.7 new partners in the prior month; in 1984, respondents reported an average of 2.5 new partners in the prior month.

7.”Increases in Unsafe Sex and Rectal Gonorrhea among Men Who Have Sex with Men — San Francisco, California, 1994-1997,” Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report, CDC, 48(03): 45-48, p. 45 (January 29, 1999).

8.This was evident by the late 80’s and early 90’s. Jeffrey A. Kelly, PhD, et al., “Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome/ Human Immunodeficiency Virus Risk Behavior Among Gay Men in Small Cities,” Archives of Internal Medicine, 152: 2293-2297, pp. 2295-2296 (November 1992); Donald R. Hoover, et al., “Estimating the 1978-1990 and Future Spread of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 in Subgroups of Homosexual Men,” American Journal of Epidemiology, 134(10): 1190-1205, p. 1203 (1991).

9.A lesbian pastor made this assertion during a question and answer session that followed a presentation the author made on homosexual health risks at the Chatauqua Institute in Western New York, summer 2001.

10.Paul Van de Ven, et al., “Facts & Figures: 2000 Male Out Survey,” p. 20 & Table 20, monograph published by National Centre in HIV Social Research Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, The University of New South Wales, February 2001.

11.Rotello, pp. 43-46.

12.Ibid., pp. 165-172.

13.Hoover, et al., Figure 3.

14.”Basic Statistics,” CDC — Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, June 2001, www.cdc.gov/hiv/stats.htm. (Nearly 8% (50,066) of men with AIDS had sex with men and used intravenous drugs. These men are included in the 64% figure (411,933) of 649,186 men who have been diagnosed with AIDS.)

15.Figures from a study presented at the Infectious Diseases Society of America meeting in San Francisco and reported by Christopher Heredia, “Big spike in cases of syphilis in S.F.: Gay, bisexual men affected most,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 26, 2001, www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/ article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2001/10/26/MN7489 3.DTL.

16.Catherine Hutchinson, et al., “Characteristics of Patients with Syphilis Attending Baltimore STD Clinics,” Archives of Internal Medicine, 151: 511-516, p. 513 (1991).

17.Katherine Fethers, Caron Marks, et al., “Sexually transmitted infections and risk behaviours in women who have sex with women,” Sexually Transmitted Infections, 76(5): 345- 349, p. 347 (October 2000).

18.James Price, et al., “Perceptions of cervical cancer and pap smear screening behavior by Women’s Sexual Orientation,” Journal of Community Health, 21(2): 89-105 (1996); Daron Ferris, et al., “A Neglected Lesbian Health Concern: Cervical Neoplasia,” The Journal of Family Practice, 43(6): 581-584, p. 581 (December 1996); C. Skinner, J. Stokes, et al., “A Case-Controlled Study of the Sexual Health Needs of Lesbians,” Sexually Transmitted Infections, 72(4): 277-280, Abstract (1996).

19.The Gay and Lesbian Medical Association (GLMA) recently published a press release entitled “Ten Things Gay Men Should Discuss with Their Health Care Providers” (July 17, 2002), www.glma.org/news/ releases/n02071710gaythings.html. The list includes: HIV/AIDS (Safe Sex), Substance Use, Depression/ Anxiety, Hepatitis Immunization, STDs, Prostate/ Testicular/Colon Cancer, Alcohol, Tobacco, Fitness and Anal Papilloma.

20.R. R. Wilcox, “Sexual Behaviour and Sexually Transmitted Disease Patterns in Male Homosexuals,” British Journal of Venereal Diseases, 57(3): 167-169, 167 (1981).

21.Robert T. Michael, et al., Sex in America: a Definitive Survey, pp. 140-141, Table 11, Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1994; Rotello, pp. 75-76.

22.Rotello, p. 92.

23.Jon M. Richards, J. Michael Bedford, and Steven S. Witkin, “Rectal Insemination Modifies Immune Responses in Rabbits,” Science, 27(224): 390-392 (1984).

24.S. S. Witkin and J. Sonnabend, “Immune Responses to Spermatozoa in Homosexual Men,” Fertility and Sterility, 39(3): 337-342, pp. 340-341 (1983).

25.Anne Rompalo, “Sexually Transmitted Causes of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Homosexual Men,” Medical Clinics of North America, 74(6): 1633-1645 (November 1990); “Anal Health for Men and Women,” LGBTHealthChannel, www.gayhealthchannel.com/analhealth/; “Safer Sex (MSM) for Men who Have Sex with Men,” LGBTHealthChannel, www.gayhealthchannel.com/stdmsm/.

26.”Resurgent Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Disease Among Men Who Have Sex With Men — King County, Washington, 1997-1999,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, CDC, 48(35): 773-777 (September 10, 1999).

27.Heredia, “Big spike in cases of syphilis in S.F.: Gay, bisexual men affected most.”

28.”Changing Patterns of Groups at High Risk for Hepatitis B in the United States,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, CDC, 37(28): 429-432, p. 437 (July 22, 1988). Hepatitis B and C are viral diseases of the liver.

29.Edward O. Laumann, John H. Gagnon, et al., The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States, p. 293, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994; Michael, et al., p. 176; David Forman and Clair Chilvers, “Sexual Behavior of Young and Middle-Aged Men in England and Wales,” British Medical Journal, 298: 1137-1142 (1989); and Gary Remafedi, et al., “Demography of Sexual Orientation in Adolescents,” Pediatrics, 89: 714-721 (1992). See appendix A.

30.Mads Melbye, Charles Rabkin, et al., “Changing patterns of anal cancer incidence in the United States, 1940-1989,” American Journal of Epidemiology, 139: 772-780, p. 779, Table 2 (1994).

31.James Goedert, et al., for the AIDS-Cancer Match Study Group, “Spectrum of AIDS-associated malignant disorders,” The Lancet, 351: 1833-1839, p. 1836 (June 20, 1998).

32.”Anal Health for Men and Women,” LGBTHealthChannel, www.gayhealthchannel.com/analhealth/; J. E. Barone, et al., “Management of Foreign Bodies and Trauma of the Rectum,” Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics, 156(4): 453-457 (April 1983).

33.Henry Kazal, et al., “The gay bowel syndrome: Clinicopathologic correlation in 260 cases,” Annals of Clinical and Laboratory Science, 6(2): 184-192 (1976).

34.Glen E. Hastings and Richard Weber, “Use of the term ‘Gay Bowel Syndrome,'” reply to a letter to the editor, American Family Physician, 49(3): 582 (1994).

35.Ibid.; E. K. Markell, et al., “Intestinal Parasitic Infections in Homosexual Men at a San Francisco Health Fair,” Western Journal of Medicine, 139(2): 177-178 (August, 1983).

36.”Hepatitis A among Homosexual Men — United States, Canada, and Australia,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, CDC, 41(09): 155, 161-164 (March 06, 1992).

37.Rompalo, p. 1640.

38.H. Naher, B. Lenhard, et al., “Detection of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in anal scrapings from HIV-positive homosexual men,” Archives of Dermatological Research, 287(6): 608- 611, Abstract (1995).

39.B. L. Carlson, N. J. Fiumara, et al., “Isolation of Neisseria meningitidis from anogenital specimens from homosexual men,” Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 7(2): 71-73 (April 1980).

40.P. Paulet and G. Stoffels, “Maladies anorectales sexuellement transmissibles” [“Sexually-Transmissible Anorectal Diseases”], Revue Medicale Bruxelles, 10(8): 327-334, Abstract (October 10, 1989).

41.”Hepatitis A among Homosexual Men — United States, Canada, and Australia,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, CDC, 41(09): 155, 161-164 (March 06, 1992).

42.Ibid.

43.C. M. Thorpe and G. T. Keutsch, “Enteric bacterial pathogens: Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter,” in K. K. Holmes, P. A. Mardh, et al., (Eds.), Sexually Transmitted Diseases (3rd edition), p. 549, New York: McGraw-Hill Health Professionals Division, 1999.

44.Tim Bonfield, “Typhoid traced to sex encounters,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 26, 2001; Erin McClam, “Health Officials Document First Sexual Transmission of Typhoid in U.S.,” Associated Press, April 25, 2001, www.thebody.com/ cdc/news_updates_archive/apr26_01/typhoid.html. A representative of the Foodborne and Diarrheal Diseases Branch, Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases at the CDC in Atlanta, Georgia, confirmed this report and provided a link to the AP story on October 4, 2002.

45.Jeffrey Martin, et al., “Sexual Transmission and the Natural History of Human Herpes Virus 8 Infection,” New England Journal of Medicine, 338(14): 948-954, p. 952 (1998).

46.Alexandra M. Levine, “Kaposi’s Sarcoma: Far From Gone,” paper presented at 5th International AIDS Malignancy Conference, April 23-25, 2001, Bethesda, Maryland, www.medscape.com/viewarticle/420749.

47.”Paraphilias,” Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision, p. 576, Washington: American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Karla Jay and Allen Young, The Gay Report: Lesbians and Gay Men Speak Out About Sexual Experiences and Lifestyles, pp. 554-555, New York: Summit Books (1979).

48.Jay and Young, pp. 554-555.

49.Sade, Marquis de, Justine or Good Conduct Well Chastised (1791), New York: Grove Press (1965).

50.Michigan Rope internet advertisement for “Bondage and Beyond,” which was scheduled for February 9-10, 2002, near Detroit, Michigan, www.michiganrope.com/ MichiganRopeWorkshop.html. The explicit nature of the advertisement was changed following unexpected publicity, and the hotel where the conference was scheduled ultimately canceled it. Marsha Low, “Hotel Ties Noose Around 2-Day Bondage Meeting,” Detroit Free Press, January 25, 2002, www.freep.com/news/locoak/ nrope25_20020125.htm.

51.Allyson Smith, “Ramada to host ‘Vicious Valentine’ Event,” WorldNet Daily, February 14, 2002, www.worldnetdaily. com/news/article.asp?ARTICLE_ID=26453; “Vicious Valentine 5 Celebrates Mardi Gras, Feb 15-17, 2002,” www.leatherquest.com/events/vv2002.htm.

52.The sadistic rape of 13-year-old Jesse Dirkhising on September 26, 1999, left him dead. See Andrew Sullivan, “The Death of Jesse Dirkhising,” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 1, 2001.

53.Jay and Young, pp. 554-555.

54.Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, “MSM: Clinician’s Guide to Incorporating Sexual Risk Assessment in Routine Visits,” www.glma.org/medical/clinical/msm_assessment. html.

55.S. Bygdeman, “Gonorrhea in men with homosexual contacts. Serogroups of isolated gonococcal strains related to antibiotic susceptibility, site of infection, and symptoms,” British Journal of Venereal Diseases, 57(5): 320-324, Abstract (October 1981).

56.As of January 1, 1999, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) estimated the cancer prevalence in the United States to be 8.9 million. “Estimated US Cancer Prevalence Counts: Who Are Our Cancer Survivors in the US?,” Cancer Control & Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, April 2002, www.cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/prevalence. In 1999, the American Cancer Society (ACS) estimated 1,221,800 new cancer cases in the US and an estimated 563,100 cancer related deaths, “Cancer Facts and Figures 1999,” p. 4, American Cancer Society, Inc., 1999, www.cancer.org/ downloads/STT/F&F99.pdf; in 2000, the ACS estimated 1,220,100 new cancer cases and 552,200 deaths from cancer, “Cancer Facts and Figures 2000,” p. 4, American Cancer Society, Inc., 2000, www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/ F&F00.pdf; in 2001, the ACS estimated a total number of 1,268,000 new cases of cancer and 553,400 deaths, “Cancer Facts and Figures 2001,” p. 5, American Cancer Society, Inc., 2001, www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/ F&F2001.pdf. This results in an estimated growth of 2,041,200 new cancer cases over the past three years and an estimated 10,941,200 people with cancer as of January 1, 2002. In 2001 there were 793,025 reported AIDS cases. “Basic Statistics,” CDC — Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, June 2001, www.cdc.gov/hiv/stats.htm.

57.The federal spending for AIDS research in 2001 was $2,247,000,000, while the spending for cancer research was not even double that at $4,376,400,000. “Funding For Research Areas of Interest,” National Institute of Health, 2002, www4.od.nih.gov/officeofbudget/ FundingResearchAreas.htm.

58.Ibid.; “Fast Stats Ato Z: Diabetes,” CDC — National Center for Health Statistics, June 04, 2002, www.cdc.gov/nchs/ fastats/diabetes.htm; “Fast Stats A to Z: Heart Disease,” CDC — National Center for Health Statistics, June 06, 2002, www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/heart.htm.

59.Gay and Lesbian Medical Association Press Release, “Ten Things Lesbians Should Discuss with Their Health Care Providers” (July 17, 2002), www.glma.org/news/ releases/n02071710lesbianthings.html. The list includes Breast Cancer, Depression/Anxiety, Gynecological Cancer, Fitness, Substance Use, Tobacco, Alcohol, Domestic Violence, Osteoporosis and Heart Health.

60.Michael, et al., p. 176 (“about 1.4 percent of women said they thought of themselves as homosexual or bisexual and about 2.8% of the men identified themselves in this way”).

61.See Appendix A.

62.Skinner, et al., Abstract; Ferris, et al. p. 581; James Price, et al., p. 90; see Appendix A.

63.Katherine Fethers, et al., “Sexually transmitted infections and risk behaviours in women who have sex with women,” Sexually Transmitted Infections, 76(5): 345-349, p. 348 (2000).

64.Ibid., p. 347.

65.Ibid.

66.Ibid.

67.Ibid., p. 348.

68.Ibid., p. 347, Table 1; Susan D. Cochran, et al., “Cancer- Related Risk Indicators and Preventive Screening Behaviors Among Lesbians and Bisexual Women,” American Journal of Public Health, 91(4): 591-597 (April 2001); Juliet Richters, Sara Lubowitz, et al., “HIV risks among women in contact with Sydney’s gay and lesbian community,” Venereology, 11(3): 35-38 (1998); Juliet Richters, Sarah Bergin, et al., “Women in Contact with the Gay and Lesbian Community: Sydney Women and Sexual Health Survey 1996 and 1998,” National Centre in HIV Social Research, University of New South Wales, 1999.

69.Fethers, et al., p. 347 and Table 1.